The Toll of the Spanish Flu in the Military and A Sampling of Lee County’s Soldiers who died Before they Could Fight the Germans in WW1

Teresa Paglione • June 16, 2020

For every American service member killed in the trenches, another 12 fell to disease, much of that caused by the Spanish flu.

World-wide, 45,000 Americans troops died from the Spanish flu and 53,400 died in combat in World War 1. Stateside, another 675,000 Americans died, more than the U.S. casualties of all the wars of the 20th century combined. Many medical historians say it's likely the virus launched itself onto the world from Haskell County, Kansas, and the United States Army helped move it along to become a worldwide killer.

In January and February 1918, local physician Loring Miner found people in sparsely populated Haskell County were coming down with a particularly violent strain of flu. Strong, healthy people died. Miner was so concerned that in March 1918 he let the U.S. Public Health Service know what he had seen and warned of a new type of flu.

In the past, the disease probably would never had spread beyond Haskell County, however in 1918 America was at war. Young men from Haskell County were training nearby at Camp Funston, what is now Fort Riley, Kansas. They reported to the camp for duty and went back and forth from home when on leave. On March 4, the first influenza cases were identified at Camp Funston. Within three weeks, 1,100 of the 56,222 troops at the camp were sick. And because the Army was constantly transporting men to camps all across the country and to Europe, the virus quickly spread. Within a month, infected soldiers had carried the flu with them to all of Europe.

During the spring of 1918 more than 130,000 of the 1.2 million soldiers just in the United States were hospitalized with flu. With the arrival of summer, the virus disappeared again, but in the fall of 1918 it had mutated and came roaring back. At Camp Devens in Massachusetts the influenza virus appeared in September. By the end of the month, 14,000 troops at the camp were sick and 757 had died.

Before the Army decided to quarantine the camp, troops had been sent to Camp Upton on Long Island. Camp Upton was where the National Guard's 42nd Division had assembled and where the 77th Division--composed of draftees from New York City--had trained. The disease appeared at Camp Upton Sept. 13. Temporary hospitals were established when the Army post’s hospital became overwhelmed with patients.

In Europe, doctors of the American Expeditionary Force hospitalized 340,000 soldiers for influenza and 227,000 soldiers due to battle wounds. In October 1918, as the American Army was locked in battle with the Germans in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, 1,451 Americans died from the flu. More 3rd Infantry Division Soldiers were evacuated from the front with influenza than from combat wounds.

The flu continued to spread and kill for nearly three agonizing years, on a scale that had not been seen since the bubonic plague wiped out at least one-third of Europe’s population in the late Middle Ages. Some 675,000 Americans died, more than the U.S. casualties of all the wars of the 20th century combined.

Soon after the Spanish flu ended and for decades after, the pandemic largely vanished from the public imagination. “Part of the problem was that dying from flu was considered unmanly. To die in a firefight -- that reflected well on your family. But to die in a hospital bed, turning blue, puking, beset by diarrhea — that was difficult for loved ones to accept. There was a mass decision to forget.”,” said Catharine Arnold, the author of “Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts From the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History.” The first major account of the flu, “Epidemic and Peace” — later reissued as “America’s Forgotten Pandemic” — was published in 1976 by Alfred Crosby.

By the War Department's most conservative count, influenza sickened 26% of the Army—more than one million men—and killed almost 30,000 before they even got to France. On both sides of the Atlantic, the Army lost a staggering 8,743,102 days to influenza among enlisted men in 1918 The Navy recorded 5,027 deaths and more than 106,000 hospital admissions for influenza and pneumonia out of 600,000 men, but given the large number of mild cases that were never recorded, Braisted put the sickness rate closer to 40%.

The Red Cross recruiting trained nurses for the Army Nurse Corps and organized ambulance companies. The Army Medical Department had 30,500 medical officers, 21,500 nurses—including 350 African American physicians but no black nurses until December 1918.

Nurses of the base hospital at Camp McClellan in Anniston, Alabama. (Photo Courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History)

In some camps, fewer African American soldiers contracted the disease but had higher mortality rates than white soldiers. Some medical officers erroneously attributed this to racial weakness and susceptibility - but segregation, ironically, may have shielded some black units from influenza infection. However, the higher mortality rate was probably due to inferior living conditions and medical care in the military. (Segregation in the Army was rarely “separate but equal.”) One study of the army rations allocated to men at camps Grant, Dodge, and Funston over four months revealed that the all-black 366th Infantry, a black combat division, received less protein and fewer calories than the white units. And had fewer doctors. - a black regiment unit that fought in the Meuse-Argonne, had only one medical officer even though there were several hundred men requiring care due to influenza and pneumonia. (Byerly 2010).

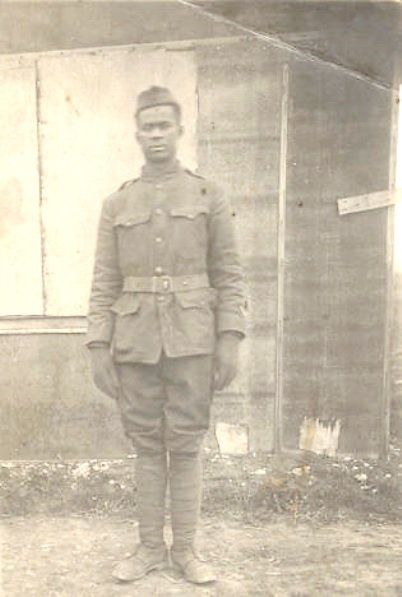

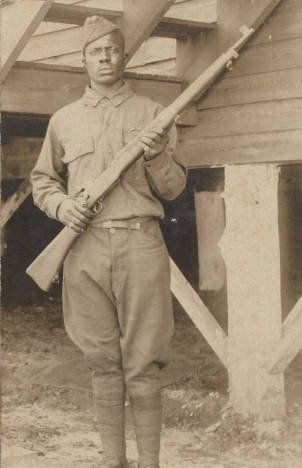

“Unidentified African American Soldier in Uniform” (WW 1). And “Possibly Bud Datcher in his military uniform.” From the Datcher Family Collection. (Photos Courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History)

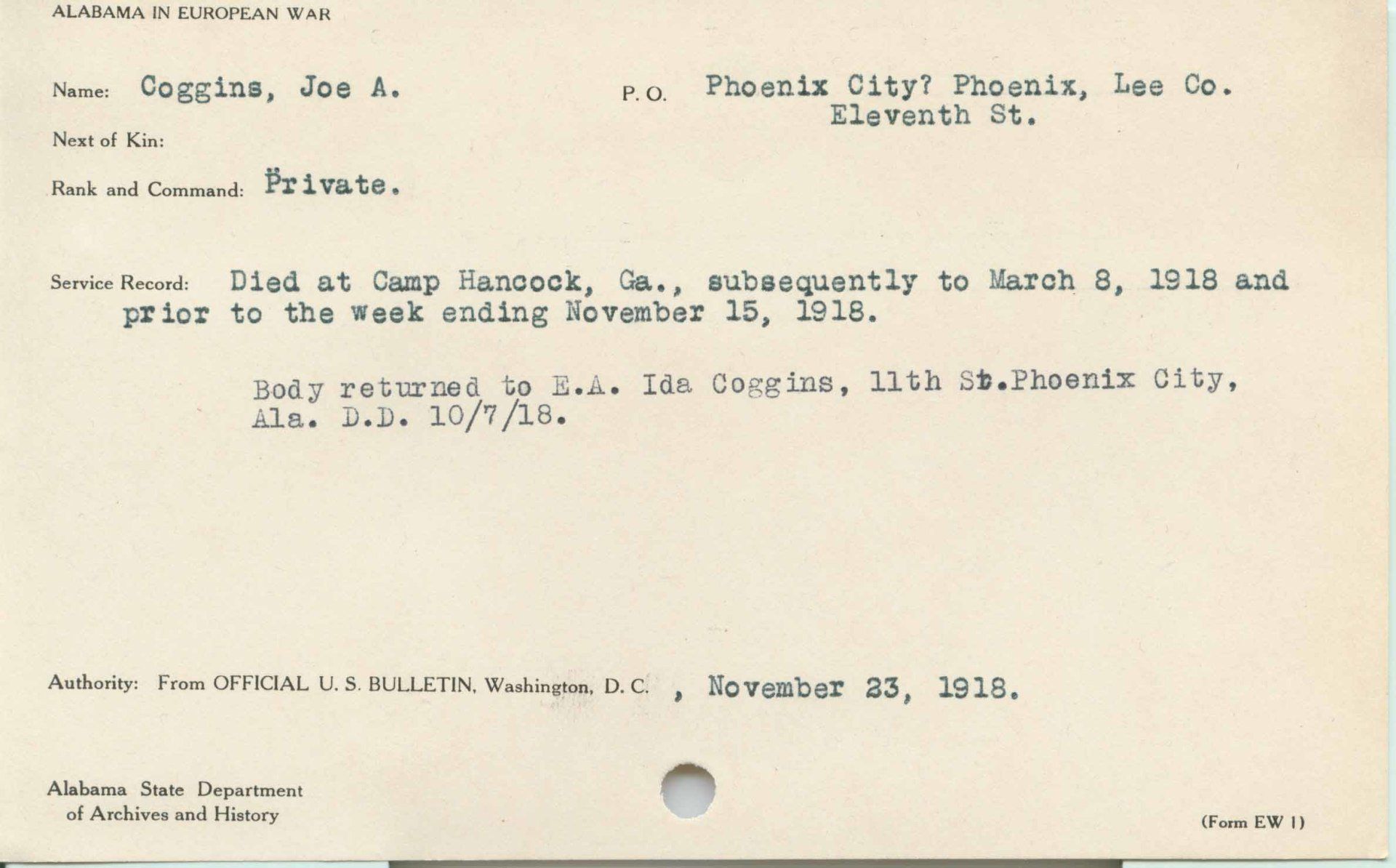

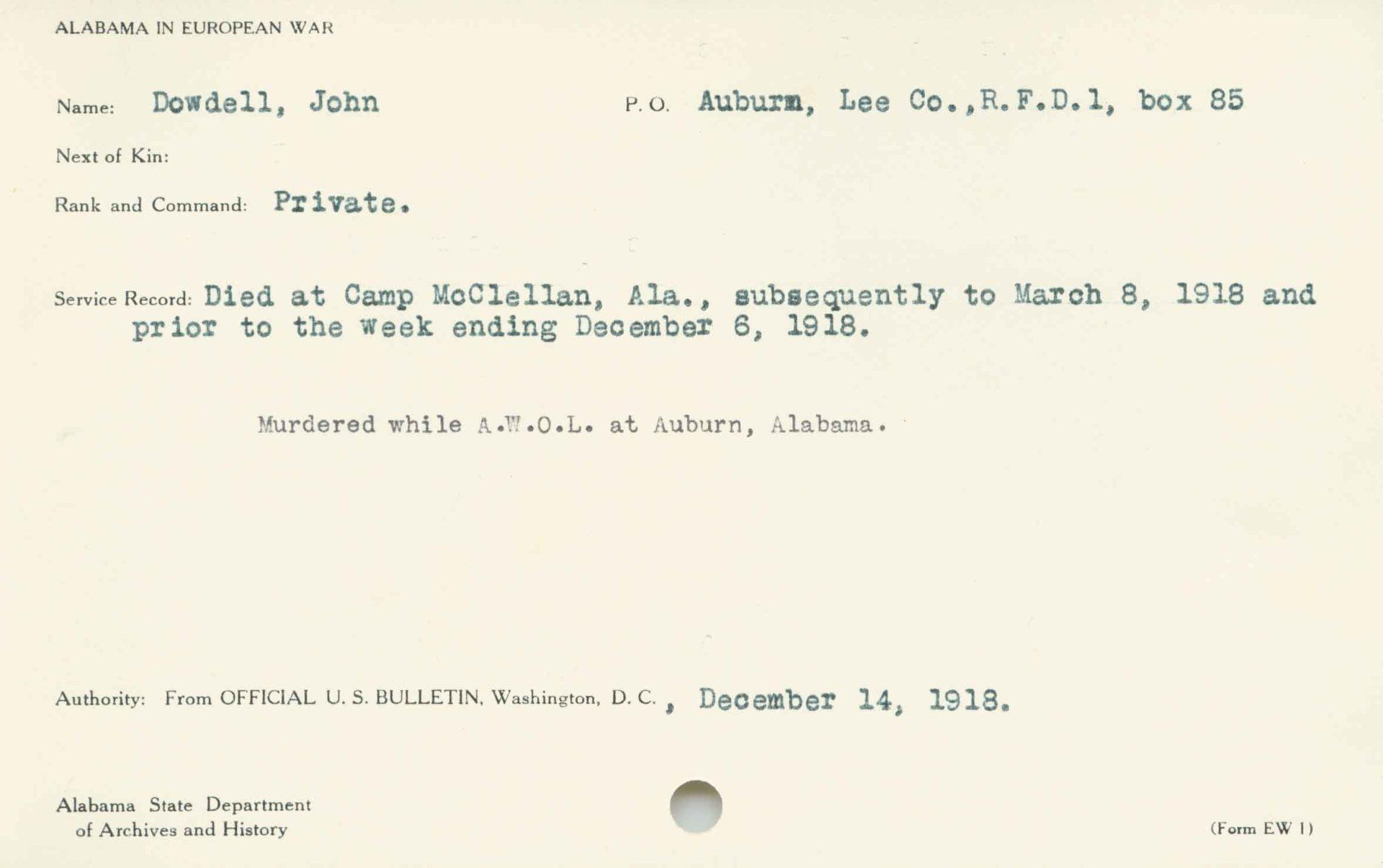

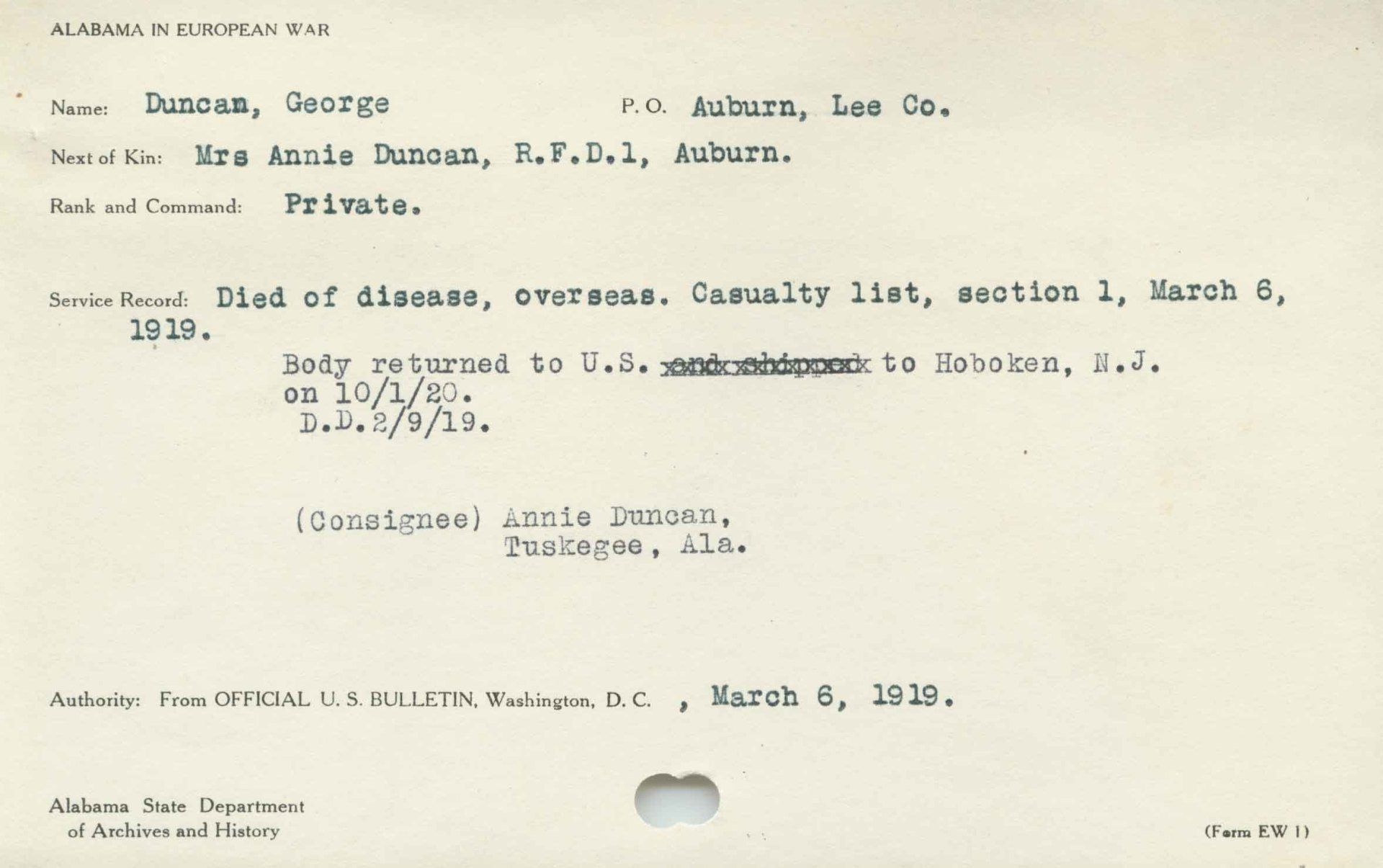

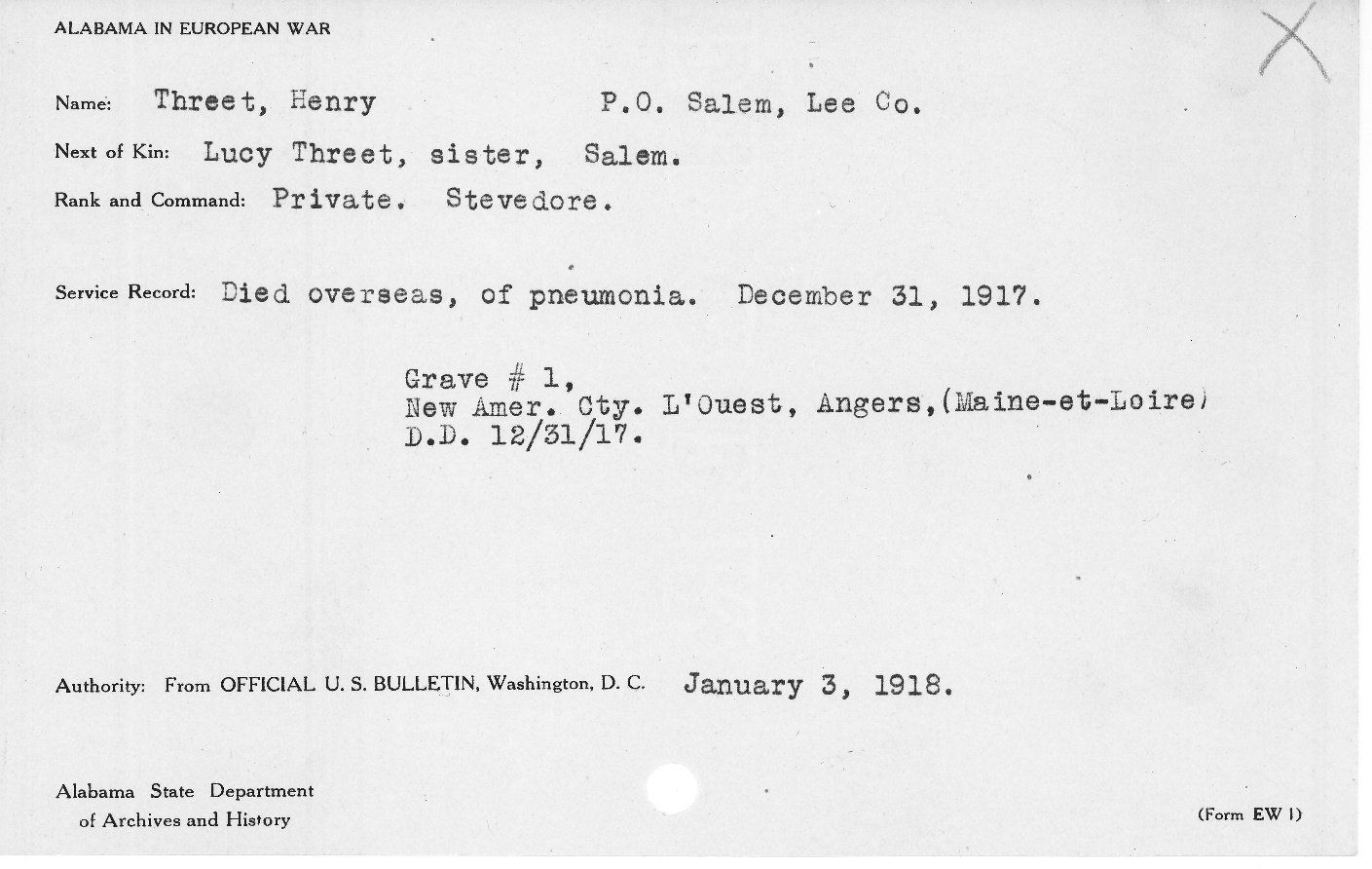

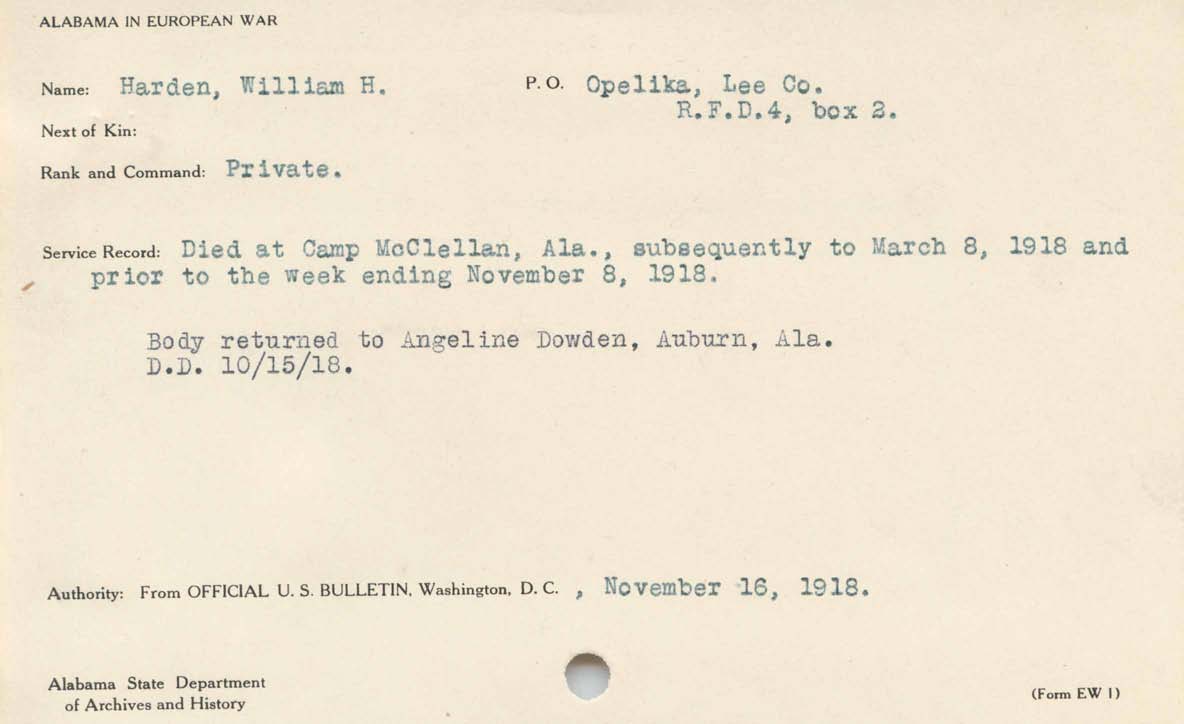

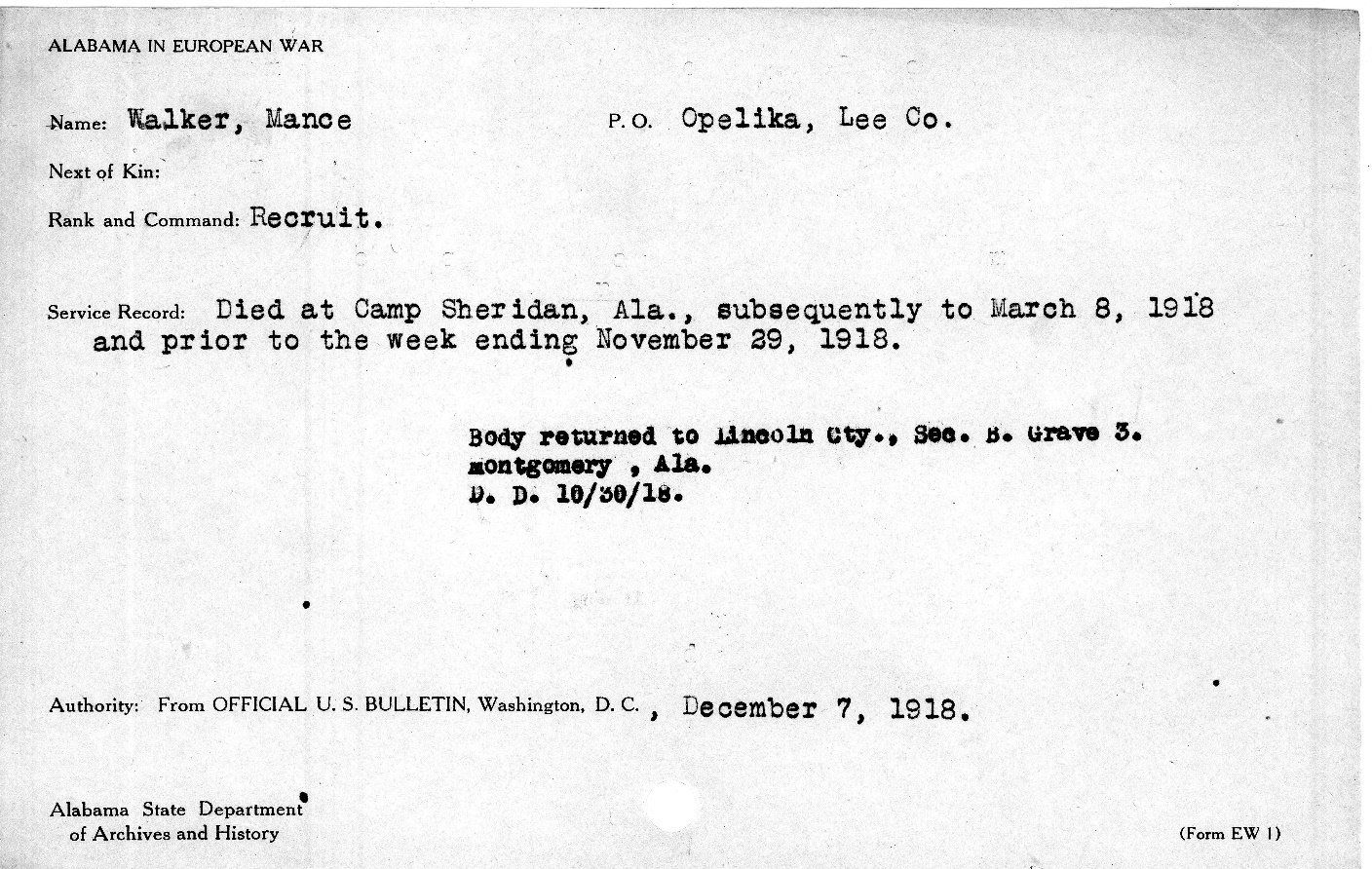

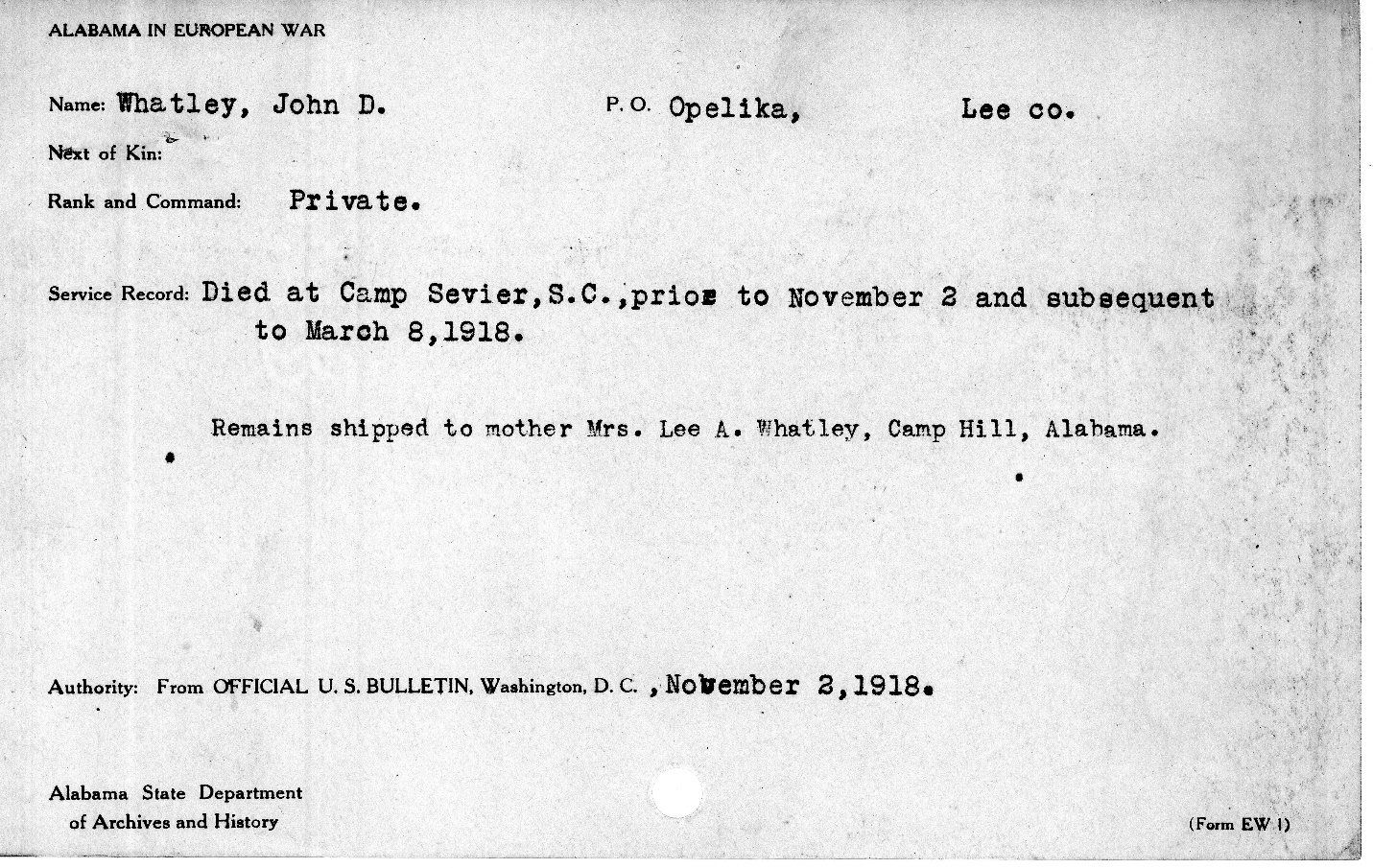

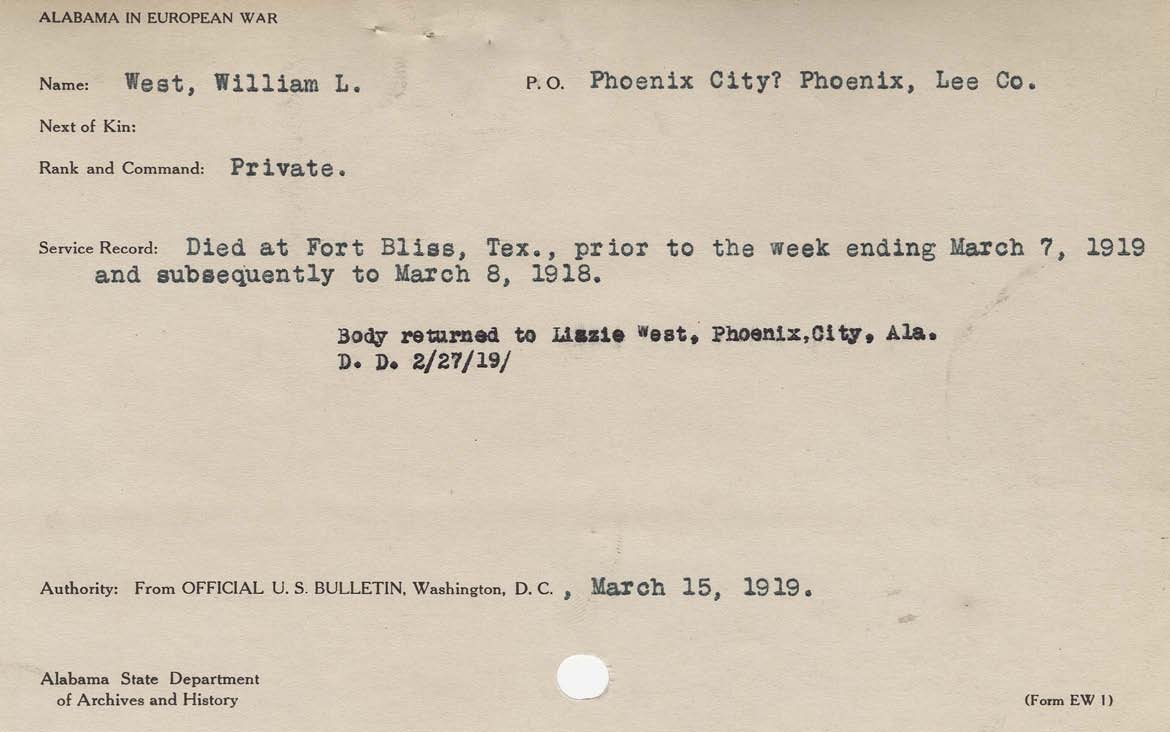

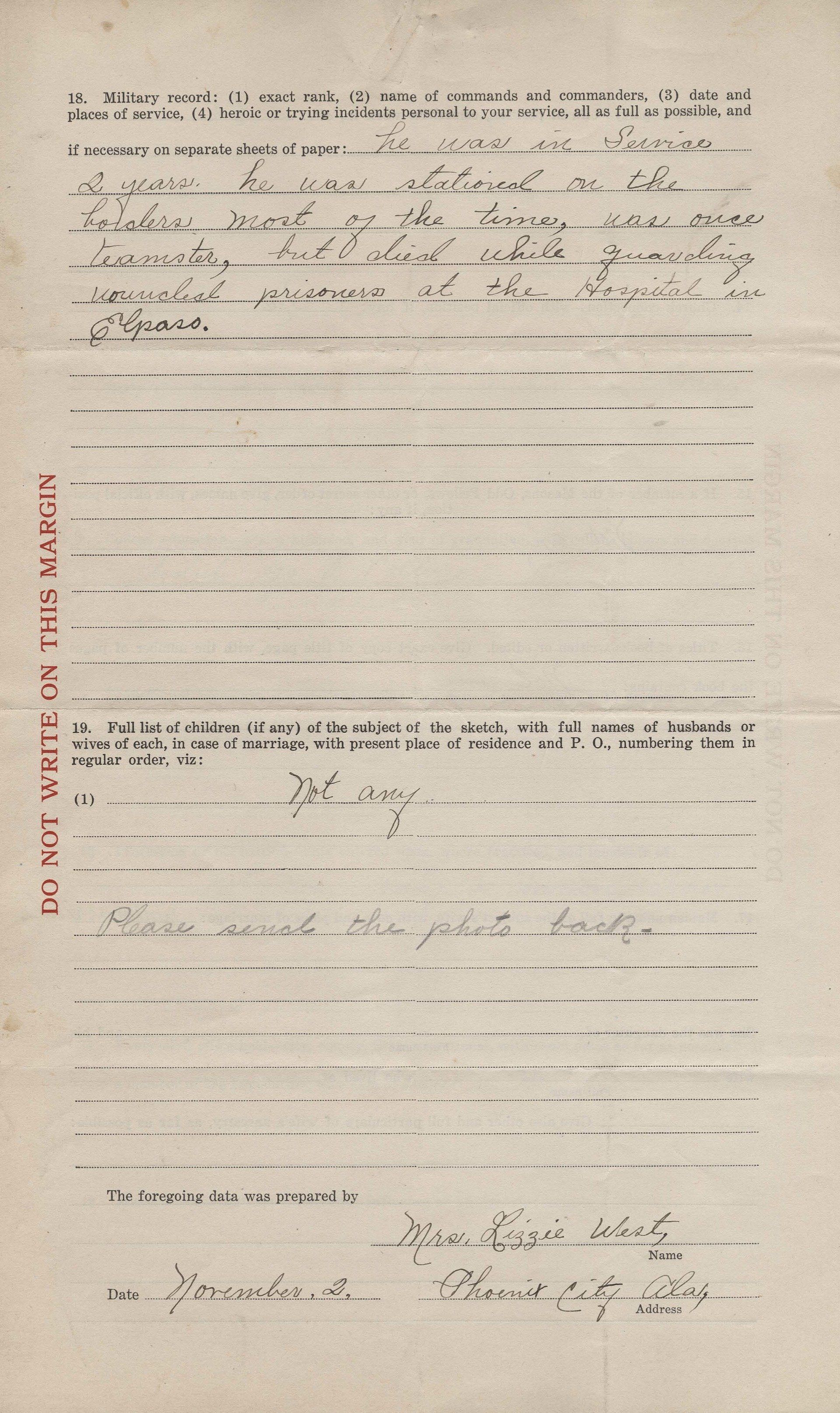

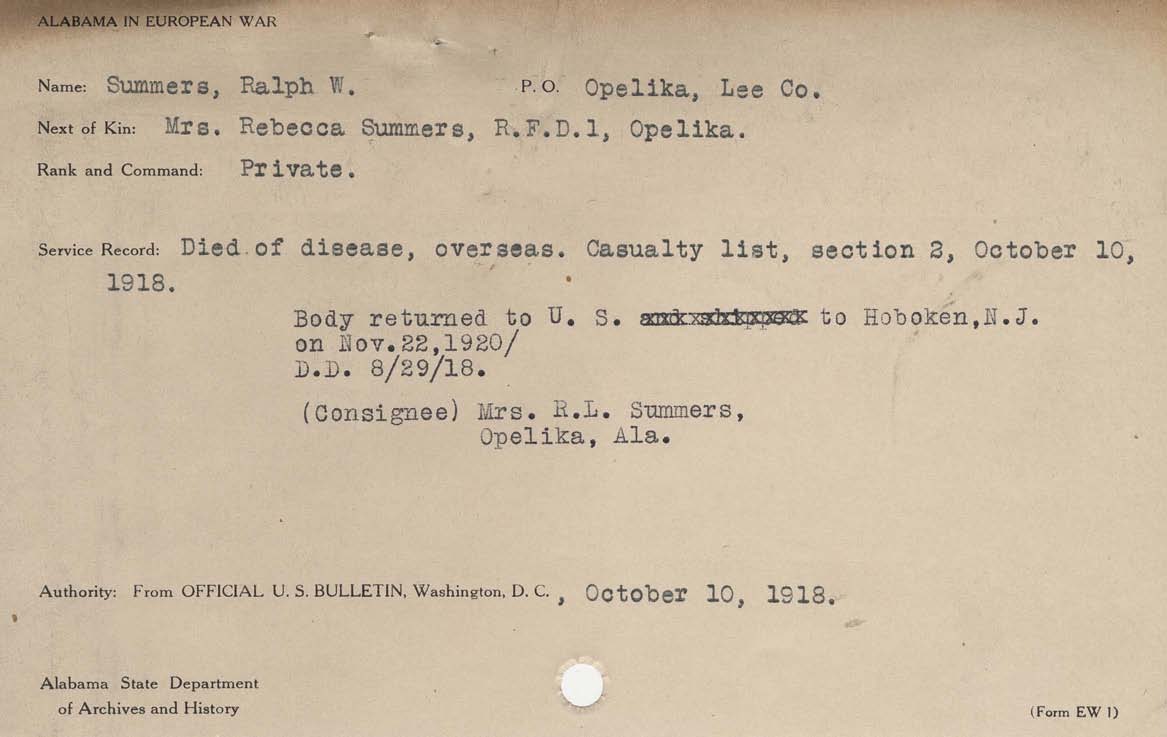

There are probably hundreds if not thousands more soldiers and sailors from Alabama that died or survived the Spanish flu; however, the following images of “Alabama in European War, Official US Bulletin” are men from Lee County listed in the digital database (online) Gold Star files at the Alabama Department of Archives and History. Some cards make no mention of the cause of death, but they are included here since it must be presumed that they died of disease – especially when still stateside. However, those killed in Europe that have no diagnosis may have died of “gas inhalation” - as the bioform for James William Bunch states…. But that is another story.

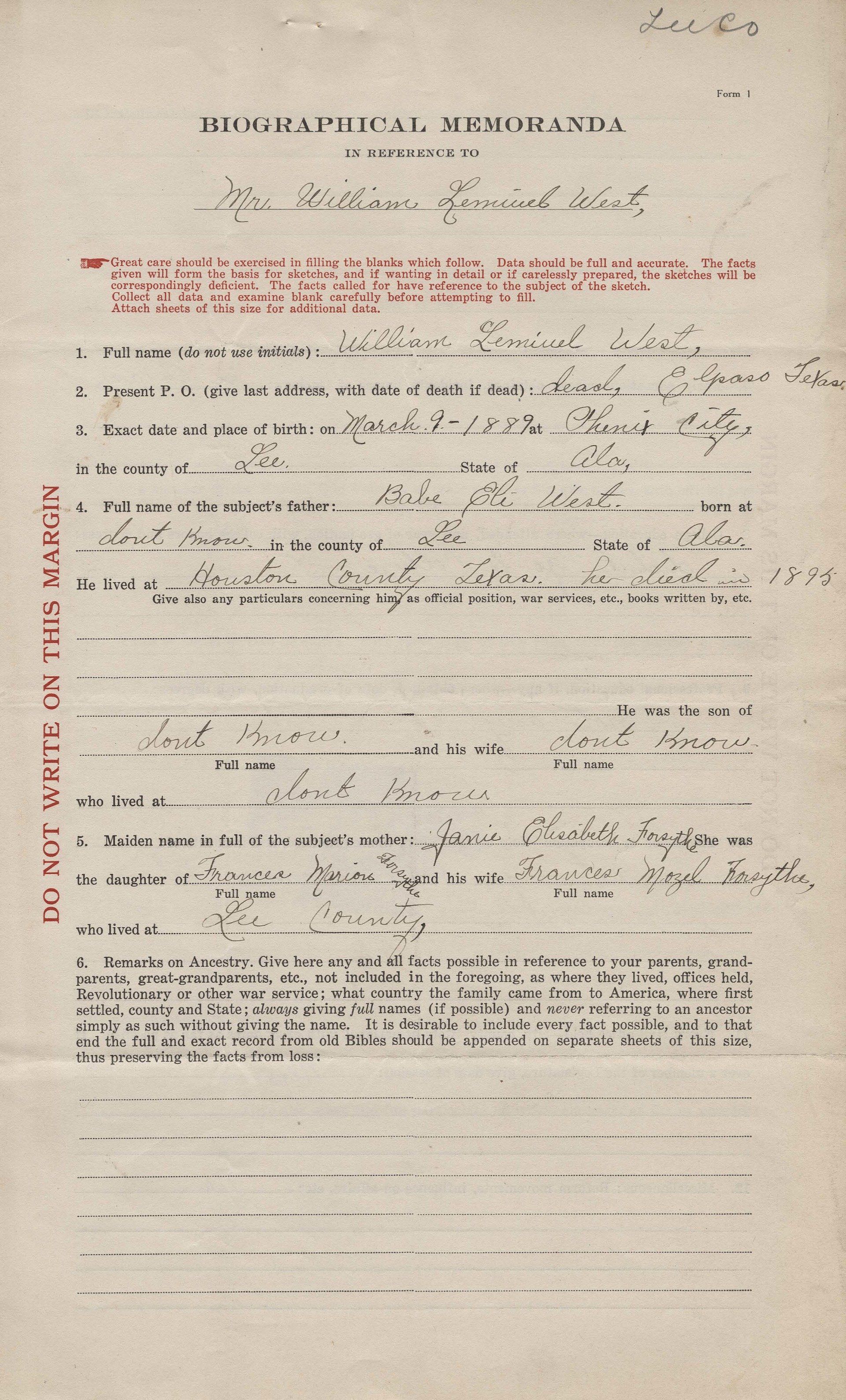

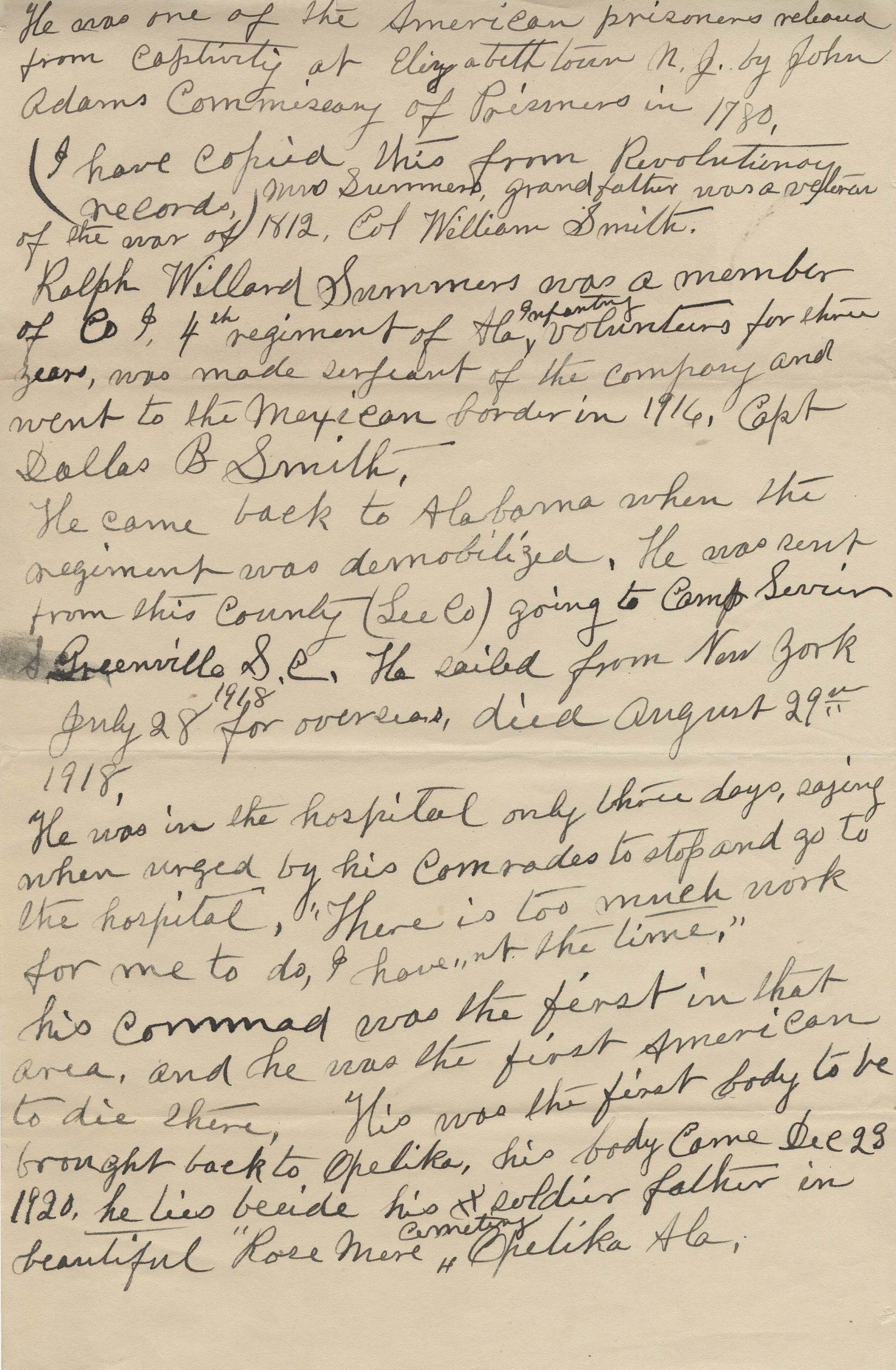

There was also one ‘bioform’ or questionnaire completed by a family member for William Lemial West that provides some simple biographical data that probably resembles thousands of other lifestories: He didn’t go to college and he had no professional degree .He was single, or as his mother wrote – “unmarried” and had no children. In the questionnaire his mother also remarked that he was “only a common laborer.” He had no particular political party affiliation and did not attend any particular church; he was not a member of any club or organization. Answering a last question, she wrote “he was in service 2 years. he was stationed on the borders most of the times, was once a teamster, but died while guarding wounded prisoners at the hospital in El Paso.”

Out of curiosity I checked ancestry.com to try to find the cause of death and found his Death Certificate, issued by the State of Texas. Private West was attached to the Medical Dept. at Fort Bliss Hospital. The certificate indicates his date of death as February 27, 1919. The attending physician stated that he first saw Private West on February 22 however he died on February 27. An examination and lab X-ray confirmed the cause of death as bronchial pneumonia.

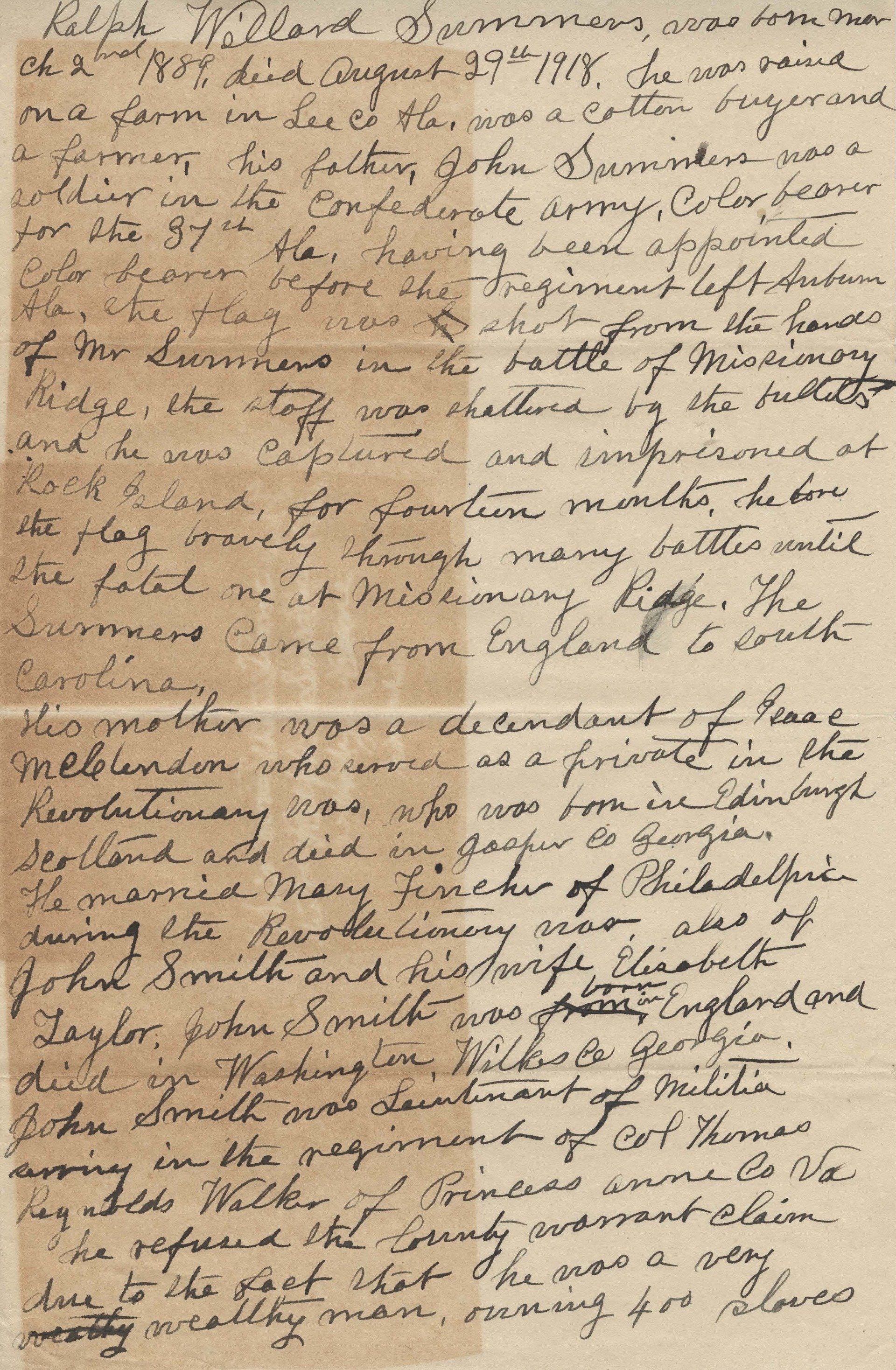

There was a letter from the mother of Ralph W. Summers in the Gold Star database attached to the card for his military service. Private Summers was listed as “died of disease, overseas.” His mother sent a letter to the Archives regaling his heritage as a descendant of a Revolutionary War soldier and multiple family members in the Civil War. She goes on to write:

Ralph Willard Summers was born March 2 1889, died August 29, 1918. He was raised on a farm in Lee Co., Ala., was a cotton buyer and farmer. His father John Summers was a soldier in the Confederate Army… Ralph Willard Summers was a member of Co 1, 4th Regiment of the Infantry Volunteers for three years, was made sergeant of the company and went to the Mexican border in 1916. He came back to Alabama when the regiment was demobilized. He was sent from this county (Lee Co) going to Camp Sevier, Greenville, SC. He sailed from New York July 28, 1918 for overseas. He died August 29th, 1918. He was in hospital only three days, saying when urged by his comrades to stop and go to the hospital – “There is too much work for me to do, I haven’t the time.” His command was the first in that area, and he was the first serviceman to die there. His was the first body to be brought back to Opelika. His body came back Dec. 23, 1920. He lies beside his soldier father in beautiful Rosemere Cemetery in Opelika, Ala.” (if you notice the dates on the card – his body was only returned to the US more than two years after his death (on Nov. 22, 1920); he was buried a month later.

References

Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Accessed June 11, 2020.

Alabama World War I Gold Star Files, Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Arnold, Catharine

2018 Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts From the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History. St. Martin's Press, NY.

Byerly, Carol R

2010 “The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919” Public Health Report. 2010;125 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):82‐91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2862337/

Durr, Eric

2018 Worldwide flu outbreak killed 45,000 American Soldiers during World War I. New York National Guard August 31 www.army.mil/article/210420/worldwide_flu_outbreak_killed_45000_american_soldiers_during_world_war_i

Segal, David

2020 “Why Are There Almost No Memorials to the Flu of 1918?” The New York Times , May 14, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/14/business/1918-flu-memorials.html?referringSource=articleShare